Over the last decade or more there has been a resurgent movement inside America’s Deep South, as well as in Texas, of whitewashing or rewriting our verifiable, factual history of the 19th-century United States by Far Right White Conservatives. These political groups and organizations are removing certain parts of history and their implied meanings of America’s less desirable, dark past from our middle and high school textbooks primarily throughout the former Confederate states and certain midwestern states.

What they have achieved already in the modern public eye and in many classrooms throughout the South and Midwest, as well as in those History/Social Studies curriculums on school campuses is that the American Civil War, fought between 1860–1865, wasn’t about slavery of the African-Americans brought here as slave-laborers to work southern plantations and carry their economic load of the American South for free. But instead they argued and argue again today that it was really about states’ rights as written in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution by our Founding Fathers. No, the latter is absolutely not true. Let’s go back and reexamine those first seven states’ “proclamations” rationalizing why they had to secede from the Union.

Why the States’ Rights Arguments are Wrong and Untrue

As late as December 2010, I repeat, 2010, many American states, primarily in the Deep South and former Confederate states, were celebrating that state’s secession (South Carolina) from the Union, from the United States of America and all the federal union stood for that our forefathers and the Founding Fathers had shed so much blood, sweat, and tears for, as well as the loss of their sons, brothers, and fathers to win independence from the tyranny of King George III and Great Britain. South Carolina, followed by six more southern states, left that united union just one generation after the American Revolution. One. And yet today many of these same descendants of the Confederacy scream “patriotic loyalty” for the USA. It does seem very perplexing that to this day in the 21st-century the Confederate South lives by a double, perhaps triple standard of what national patriotism means and represents.

But on the contrary, history shows abundantly that the South’s definition of national patriotism is cloaked and veiled in hypocrisy, rationalization, and double standards, back then and still today.

Alexander H. Stephens —

Under the newly formed Confederate States of America, Vice-President Stephens in a speech in Savannah, Georgia, March 21, 1861, explicitly articulated that the Confederacy’s foundation was the staunch belief that:

“…the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery – submission to the superior race – is his natural and normal condition”

There is no misunderstanding by what Mr. Stephens was laying out as the basic ideology of the Confederacy: racial inequality. Period. If you so desire and see fit to read Mr. Stephen’s entire Cornerstone Speech and verify this history, then click here: American Battlefield Trust – Civil War. The essential fact to remember from this speech is that Stephens tied slavery to race, making perfectly clear that the cornerstone of the new Confederacy was not just vassal slavery, but the total subordination of black people for the benefit of white people. In a twist of historical irony the Confederacy was indeed the political ancestor of Nazi Germany and apartheid-era South Africa—regimes founded on the assumption of the racial and ethnic superiority of the white ruling class and the utter inferiority and subordination of other non-white races and groups. Furthermore, VP Stephens as he often did was incorrectly attributing and maligning this Southern ideology to Thomas Jefferson and Jefferson’s resident slaves.

South Carolina’s Justification for Secession —

VP Alexander Stephens only reiterated South Carolina’s declaration explaining the rhetoric as to why it was abandoning the United States of America. Following is the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (1861):

“A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that that “Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,” and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.”

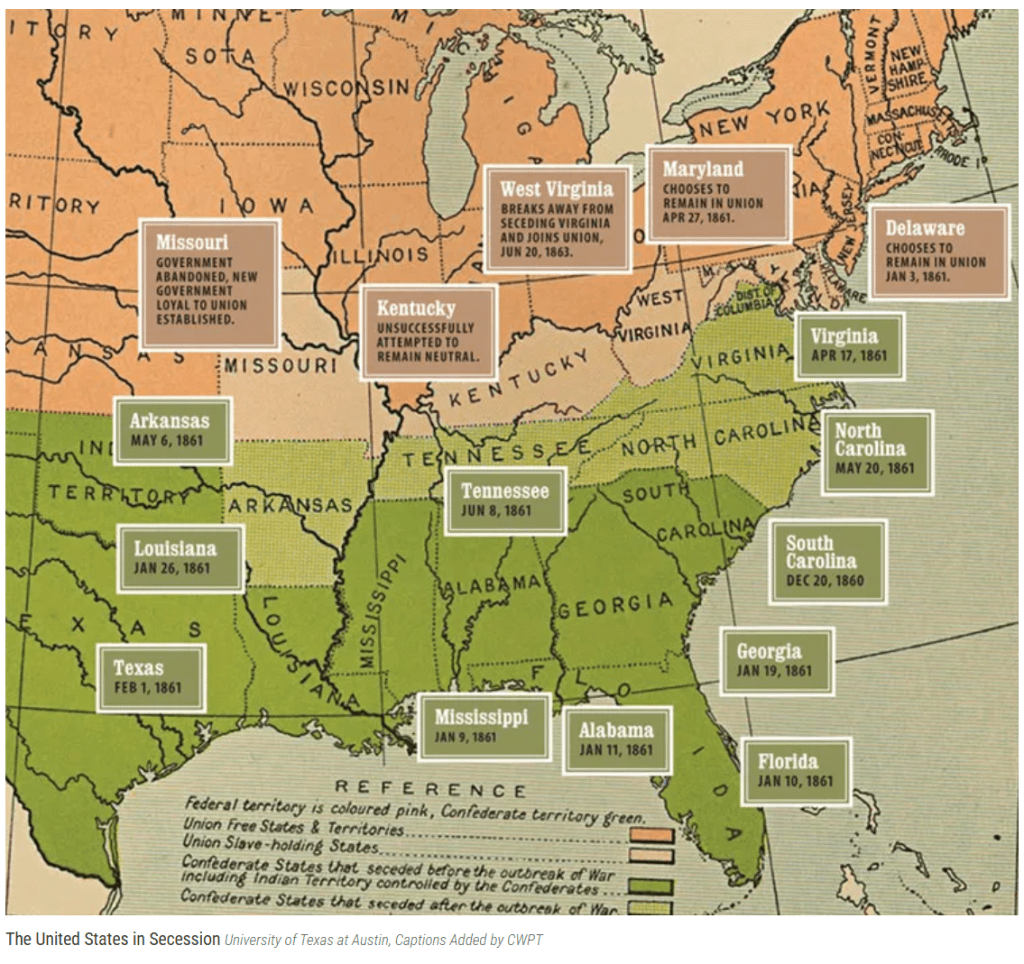

Once fighting and war broke out, Mississippi followed suit on January 9, 1861, followed by Florida January 10th, Alabama January 11th, and Georgia January 19th. Mississippi and Georgia made the same declarations. Emphatically Mississippi stated in their second sentence of their Declaration of Secession:

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.”

And Georgia did the exact same thing second sentence of their Declaration of Secession from the United States:

“For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery. They have endeavored to weaken our security, to disturb our domestic peace and tranquility, and persistently refused to comply with their express constitutional obligations to us in reference to that property, and by the use of their power in the Federal Government have striven to deprive us of an equal enjoyment of the common Territories of the Republic. This hostile policy of our confederates has been pursued with every circumstance of aggravation which could arouse the passions and excite the hatred of our people, and has placed the two sections of the Union for many years past in the condition of virtual civil war.”

Today, the relationship between secession and states’ rights is more often misunderstood and not based in the historical method or proper interpretation, especially by those who argue that the Confederate slave states seceded from the Union to ‘protect their states’ rights.’ But here’s the rub, the states which left the United States never maintained that they were being denied their “states’ rights”—that the national government had eliminated the lines been between national authority and state authority. Nor did the South complain that the federal government was too powerful and so it threatened the sovereignty of the Confederate state governments. On the contrary, the southern states complained that the northern states were pushing their states’ rights upon the southern states and the federal government in Washington D.C. wasn’t strong enough to counter or stop the North’s claims. Additionally, secessionists weren’t complaining that an overly oppressive federal government was violating their civil liberties of southern peoples; rather it was the federal government’s refusal to check and suppress the northern states’ civil liberties. Let’s examine this more closely.

The 1850’s: Substantial Pro-Slavery Advancements in the United States —

This decade in American history was a time of striking movements for pro-slavery states. They came in three major areas of law: 1) recovery of fugitive slaves back to their slave owners, 2) slavery into new and newest territories in the nation’s westward expansion, and 3) slave owners rights to travel the country with slaves even into non-slave (free) states. In fact, all three branches of our federal government passed legislation to expand the rights of slave owners! Moreover, the federal government drastically restricted the rights of free black slaves. The U.S. Supreme Court’s infamous decision in the Dred Scott Case of 1857 is one such example; it denied citizenship to people of African descent, whether enslaved or free, and declared the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional.

The United States had acquired vast amounts of land from Mexico, but the area was closed to slavery due to the Wilmot Proviso of 1846 which banned slavery from new territories. During the Mexican War, the House of Representatives passed the Proviso, but it never made it through the Senate, where the Confederate South had a majority at the time.

Also in the 1850s, supporters of slavery won huge victories in Congress, which legalized slavery throughout the west. Congress further protected the rights of masters to recover fugitive slaves with a new and powerfully nationalistic fugitive slave law. Added to this were Supreme Court decisions which made slavery a specially protected institution under the Constitution, allowing slavery in all the federal territories, concluding that free blacks had virtually no rights under the Constitution and could never be considered citizens of the United States, and finally undermined the right of free states to emancipate visiting slaves.

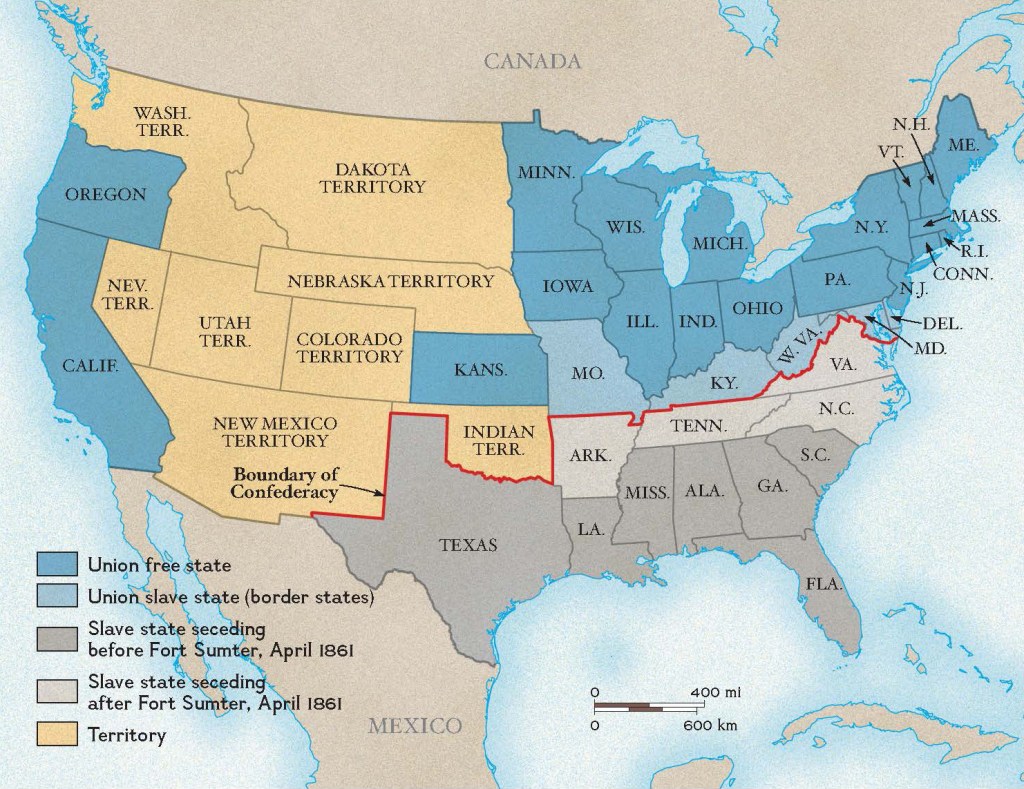

Another milestone for the Confederacy was the admission of Florida on March 3, 1845 giving the South a one state majority in the Senate. Texas’ admission on December 29, 1845 gave the South a two state majority in the Senate and the South maintained this two state majority until December 28, 1846 when Iowa was admitted into the Union, then Wisconsin (1848), and finally California in 1850 which ended the parity inside the U.S. Senate. California’s admission into the Union and Mexican territorial cession, it also made possible new slaves states entering the Union in the southwest. President Abraham Lincoln and the Union had to stop it.

The Compromise of 1850 —

This compromise was a series of legislative bills addressing issues related to slavery and slave owners. These bills granted slavery be decided by popular sovereignty with the admission of new states, prohibited slave trade in the District of Columbia, settled a Texas boundary dispute, and established a stricter Fugitive Slave Act. While intended to resolve North-South tensions, the Compromise of 1850 ultimately proved more disruptive. The Fugitive Slave Act, in particular, angered many in the North, while the South felt it didn’t go far enough to protect their interests. The compromise delayed the inevitable conflict, but did not resolve the fundamental issue of slavery, contributing to the build-up of tensions that eventually led to the Civil War at Ft. Sumter, South Carolina in 1861.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, followed by several landmark Supreme Court decisions from the late 1840’s and 1850’s, the Confederate South and its slave owners made huge gains, for all intents and purposes, by winning all the Supreme Court’s slave cases, set the nation on a path of no return to a long, deadly, bloody civil war.

Confederate Secession and States’ Rights

After a decade of remarkable success at the national level, in 1860-61 the most aggressive proslavery politicians led their states out of the Union. Were they concerned about states’ rights? Was the right of the states to control their own domestic institutions at the heart of secession? The answer is clearly no.

There is not a single historical example of the loss of states’ rights that any southerners could protest about. The federal government never threatened to end slavery in the states or even interfere with it where it existed already. Moreover, in his first inaugural address March 4, 1861, Lincoln reaffirmed this while quoting his own party’s platform on this point:

“Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that—

I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.

Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations and had never recanted them; and more than this, they placed in the platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read:

“Resolved, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the

States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.” ”

— President Abraham Lincoln, 1861

The most important and prevalent state right that any of the southern states ever claimed was that they had the “right” to secede. Secessionists claimed that this right was rooted in the inherent sovereignty of the states. South Carolina noted that the Federal Government’s “encroachments upon the reserved rights of the States, fully justified” the state in “withdrawing from the Federal Union” and that “now the State of South Carolina” had “resumed her separate and equal place among nations.” However, the tangible reasons for secession were not the rights of the states, no. While rhetorically South Carolina and other seceding states may have claimed that the national government had “encroached” on their “reserved rights,” none of the seceding states offered any examples of this, because in fact there were none. Instead, all of the Confederacy’s examples—the reasons they offered to justify secession—were purely about national policy involving slavery in the territories, the admission of new slave states, John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, northern opposition to slavery, the refusal of northern states to aggressively help in the return of fugitive slaves, and the other actions by northern state governments that were “hostile” to slavery. Most of these protests were not in fact about the federal government encroaching on southern states’ rights, but rather they were protests that the federal government had note ‘impinged on northern states’ rights.’ But this was a Confederate diversion and veiled declaration that on the surface portrayed falsely one thing, but was actually about slavery and slave owner rights. Nothing else.

Therefore, there were four obvious ironies and outright deception by the South’s later purported states’ rights controversies and their later fabricated justifications of secession from the United States that are not well detected, understood, or equitably studied by Americans, even today in the South.

First, because the Constitution of 1787 was strongly protective of slavery, and the Supreme Court amplified this protection, there was an obvious direct link to pro-slave nationalism. This meant that, before 1861, slave states didn’t require to have a states’ rights ideology to protect their most important social and economic slave institutions. A federal position did that for them. Most of their complaints about the federal government and slavery in the secessionist documents of all first seven Confederate states were not about the federal government impinging on southern states’ rights. For example, South Carolina complained that the northern states were not helping to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, and thus “laws of the General Government have ceased to effect the objects of the Constitution.” Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine, all knew full well that in order to have all thirteen colonies ratify the new U.S. Constitution in 1787 they were sacrificing total equality, liberties, and rights for all American persons, including Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians too, as alluded to in the Declaration of Independence, as well as for (or not contesting) slavery, for an immediate compromise and ratification of the Constitution for ALL thirteen colonies as one nation. The core Founding Fathers aforementioned in a sense looked the other way on the boiling problem of Southern slavery in order to get full ratifications. This does not include the problem of religion in the First Amendment which was nicely solved by the Separation of Church and State, temporarily.

Those core Founding Fathers though pleased with the Constitution’s ratification, they were not thrilled so much about several unaddressed problems. They knew just how fragile and brittle their new nation would be because total equality, liberties, and rights for all American peoples was missing or too vague and not resolved clearly and succinctly. On September 8, 1787, on the last day of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a lady asked Dr. Benjamin Franklin:

Elisabeth Powel: “Well Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?”

Dr. Franklin: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

“A republic, if you can keep it.” In this case here, how prophetic a response by Dr. Franklin when 1860-61 rolls around. That ignored slavery mess, so to speak, soon became a powder house ready for the smallest spark.

Second, because our U.S. Constitution was proslavery and supporters of slavery (including several of the Founding Fathers), slavery governed the federal government almost continuously from 1801 until 1861, the most critical supporters of states’ rights in the Antebellum Period were northern oppositions of slavery. Northerners had to assert states’ rights in order to preserve their free blacks from recurring kidnappings from southern bounty hunters and defend their fugitive slave neighbors from being chained-up, beaten, and returned to bondage. Thus, starting in the 1820s, most free states passed individual liberty laws, which annoyed the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 for southern slave owners.

In the 1830s, courts in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania upheld state exclusive, black liberty laws which undermined the 1793 law and in effect held that the 1793 law was unconstitutional, in part on states’ rights grounds for the North. In the early 1840s, Governor William H. Seward of New York and three successive governors of Maine spurned to surrender northern free blacks for helping slaves escape sought by the South’s slave owners. Just before the Civil War, Governors Salmon P. Chase and William Dennison of Ohio also refused to surrender a free black who had helped a slave escape. These northern governors rested their actions tit for tat reprisals on states’ rights arguments. Finally, after the Supreme Court brought down the first wave of northern personal liberty laws in Prigg vs Pennsylvania, many northern states responded with new laws, like the South’s, which simply withdrew all northern cooperation in the return of fugitive slaves. This was a variant of states’ rights philosophy. In these laws, passed in the 1840s and more so in the next decade after the adoption of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, the northern states took the position that their states no obligation by law to cooperate with the federal government. In doing so, the North made enforcement of the 1850 law quite difficult, or in some places, practically impossible.

Third, it should be known that the most pushy “states’ rights” arguments of the Antebellum decade in truth came from northerners, not southerners, particularly judges in Ohio, New York (Lemmon v The People), and most of all Wisconsin (Abelman v Booth). In response to the Oberlin-Wellington deliverance in Ohio, that state’s supreme court came within one vote of causing a clash with the federal government by issuing a writ of habeas corpus directed at the U.S. Marshal in Cleveland. The Wisconsin Supreme Court was not so discreet and in fact issued a writ of habeas corpus that forced U.S. Marshall Stephen Ableman to relinquish the abolitionist Sherman Booth after he had been arrested for helping rescue a fugitive slave. In New York, in Lemmon v. The People, the state’s highest court rejected any measure of courtesy towards visiting southerners. Here, the state emancipated eight Virginia slaves who were brought into the state for just long enough to take the next steamboat to New Orleans. They were in the city only because New York was the only east coast port that had direct passage to New Orleans. The decision in Lemmon was valid within the context of American constitutional law and state police powers. But, southerners believed this decision, and similar ones in other states, violated the spirit of the Union and the courtesy that should be given to citizens of other states. In addition, some southerners believed the decision in Lemmon actually breached the Commerce Clause or the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution because it denied southerners the right to travel throughout the United States with their constitutionally protected property and it interfered with “interstate commerce,” i.e. slave trading of say cattle and negro free-labor services for wealthy, lazy white southern supremist plantation owners.

The last months of the Civil War and Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant’s final two greatest victories over Robert E. Lee and the Confederate States of America, who were merely rebels, not a recognized nation anywhere, ends the bloodshed and abolishes slavery in the United States forever… well, sort of.

Final Verdict on Today’s “States Rights” or Slavery Argument

Given this short examination of the reasons and justifications of the 1860 Confederate South’s right to secede from the United States because of states rights violations by the North, all one must do is go to the Library of Congress and closely read the secession declarations of South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee (all in that order) to see with your own eyes the false arguments of today’s pro-South, pro-Confederacy (White) state residents are unequivocally NOT historically factual; not even close. Plain and simple the American Civil War and secessionist southern states was about ONE thing and one thing only:

SLAVERY.

Nothing else, nothing more. Period. End of debate.

The Professor’s Convatorium © 2023 by Professor Taboo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0