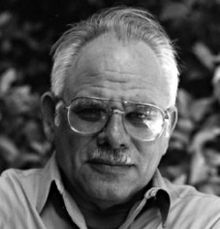

I read this post on Dr. Bart Ehrman’s blog yesterday — twice as a matter of fact — and there is just no way I can skip it and not let it follow-up my own post April 1, 2018: April Fool’s Everyone! Dr. Ehrman essentially echoes most everything I’ve posted and commented about Christendom, its very distorted and amputated history throughout its two millenia of existence, and how Christianity became the misguided monstrosity it is today. This is just too good to pass up. Therefore, I am simply going to repost what the acclaimed scholar wrote himself about Easter, or the modern myth that is the resurrection missing body of a Jewish reformer. Here is Dr. Bart Ehrman’s post:

∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ § ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼

“It is highly ironic, but relatively easy, for a historian to argue that Jesus himself did not start Christianity. Christianity, at its heart, is the belief that Jesus’ death and resurrection brought about salvation, and that believing in his death and resurrection will make a person right with God, both now and in the afterlife. Historical scholarship since the nineteenth century has marshalled massive evidence that this is not at all what Jesus himself preached.

Yes, it is true that in the Gospels themselves Jesus talks about his coming death and resurrection. And in the last of the Gospels written, John, his message is all about how faith in him can bring eternal life (a message oddly missing in the three earlier Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke).

These canonical accounts of Jesus’ words were written four, five, or six decades after his death by people who did not know him who were living in different countries, and who were not even speaking his own language. They themselves acquired their accounts of Jesus’ words from earlier Christian storytellers, who had been passing along his sayings by word of mouth, day after day, year after year, decade after decade. The task of scholarship is to determine, if possible, what Jesus really said given the nature of our sources.

Fundamentalist scholars have no trouble with the question. Since they are convinced that the Bible is the inspired and inerrant word of God, then anything Jesus is said to have said in the Gospels is something that he really said. Viola! Jesus preached the Christian faith that his death and resurrection brought salvation.

Critical scholars, on the other hand, whether they are Christian or not, realize that it is not that simple. As Christian story tellers over the decades reported Jesus’ teachings, they naturally modified them in light of the contexts within which they were telling them (to convert others for example) and in light of their own beliefs and views. The task is to figure out which of the sayings (or even which parts of which sayings) may have been what Jesus really said.

Different scholars have different views of that matter, but one thing virtually all critical scholars agree on is that the doctrines of Jesus’ saving death and resurrection were not topics Jesus addressed. These words of Jesus were placed on his lips by later Christian story-tellers who *themselves* believed that Jesus had been raised from the dead to bring about the salvation of the world, and who wanted to convince others that this had been Jesus’ plan and intention all along.

My own view is one I’ve sketched on the blog many a time before. Jesus himself – the historical figure in his own place and time – preached an apocalyptic message that God was soon to intervene in history to overthrow the powers of evil and destroy all who sided with them; he would then bring a perfect utopian kingdom to earth in which Israel would be established as a sovereign state ruling the nations and there would be no more pain, misery, or suffering. Jesus expected this end to come soon, within his own generation. His disciples would see it happen – and in fact would be rulers of this coming earthly kingdom, with him himself at their head as the ruling monarch.

It didn’t happen of course. Instead, Jesus was arrested for being a trouble maker, charged with crimes against the state (proclaiming himself to be the king, when only Rome could rule), publicly humiliated, and ignominiously tortured to death.

This was not at all what the disciples expected. It was the opposite of what they expected. It was a radical disconfirmation of everything they had heard from Jesus during all their time with him. They were in shock and disbelief, their world shattered. They had left everything to follow him, creating hardship not only for themselves but for the families near and dear to them – leaving their wives and children to fend for themselves and doubtless to suffer want and hunger with the only bread-winner away from home to accompany an itinerant preacher who thought the end of history was to arrive any day now.

This reversal of the disciples’ hopes and dreams then unexpectedly experienced its own reversal. Some of them started saying that they had seen Jesus alive again. In the Gospels themselves, of course, all the disciples see Jesus alive and are convinced that he has been raised from the dead. It is not at all clear it actually happened that way. The accounts of the Gospels are hopelessly at odds with each other about what happened, to whom, when, and where. So what can we say historically?

One thing we can say with relative certainty (even though most people – including lots of scholars!) have never thought about this or realized it, is that no one came to think Jesus was raised from the dead because three days later they went to the tomb and found it was empty. It is striking that Paul, our first author who talks about Jesus’ resurrection, never mentions the discovery of the empty tomb and does not use an empty tomb as some kind of “proof” that the body of Jesus had been raised.

Moreover, whenever the Gospels tell their later stories about the tomb, it never, ever leads anyone came to believe in the resurrection. The reason is pretty obvious. If you buried a friend who had recently died, and three days later you went back and found the body was no longer there, would your reaction be “Oh, he’s been exalted to heaven to sit at the right hand of God”? Of course not. Your reaction would be: “Grave robbers!” Or, “Hey, I’m at the wrong tomb!”

The empty tomb only creates doubts and consternation in the stories in the Gospels, never faith. Faith is generated by stories that Jesus has been seen alive again. Some of Jesus’ followers said they saw him. Others believed them. They told others — who believed them. More stories began to be told. Pretty soon there were stories that all of them had seen him alive again. The followers of Jesus who heard these stories became convinced he had been raised from the dead.

Jesus himself did not start Christianity. His preaching is not what Christianity is about, in the end. If his followers had not come to believe he had been raised from the dead, they would have seen him as a great Jewish prophet who had a specific Jewish message and a particular way of interpreting the Jewish scripture and tradition. Christianity would have remained a sect of Judaism. It would have had the historical significance of the Sadducees or Essenes – highly significant for scholars of ancient religion, but not a religion that would take over the world.

It is also not the death of Jesus that started Christianity. If he had died and no one believed in his resurrection, his followers would have talked about his crucifixion as a gross miscarriage of justice; he would have been another Jewish prophet killed by God’s enemies.

Even the resurrection did not start Christianity. If Jesus had been raised but no one found out about it or came to believe in it, there would not have been a new religion founded on God’s great act of salvation.

What started Christianity was the Belief in the Resurrection. It was nothing else. Followers of Jesus came to believe he had been raised. They did not believe it because of “proof” such as the empty tomb. They believed it because some of them said they saw Jesus alive afterward. Others who believed these stories told others who also came to believe them. These others told others who told others – for days, weeks, months, years, decades, centuries, and now millennia. Christianity is all about believing what others have said. It has always been that way and always will be.

Easter is the celebration of the first proclamation that Jesus did not remain dead. It is not that his body was resuscitated after a Near Death Experience. God had exalted Jesus to heaven never to die again; he will (soon) return from heaven to rule the earth. This is a statement of faith, not a matter of empirical proof. Christians themselves believe it. Non-Christians recognize it as the very heart of the Christian message. It is a message based on faith in what other people claimed and testified based on what others claimed and testified based on what others claimed and testified – all the way back to the first followers of Jesus who said they saw Jesus alive afterward.”

∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ § ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼

Here was my comment and question for Dr. Ehrman. He usually gets back to me within a quick, reasonable timeframe:

Dr. Ehrman, a wonderful summary of today’s meaning of Easter in modern Christian churches. Well done. Thank you.

As your colleague, Dr. James Tabor has studied, written and published, Paul/Saul and his Christology is a major force in spreading and growing the Gentile/pagan side of the “faith.” When I super-impose the full context of the Hellenistic Roman Empire and geopolitical and socioreligious infrastructure over and onto Second Temple Judaism and the Messianic Era, to me personally the gradual and eventual overshadowing (and eventual success) of Paul’s “Neo-Religion” opened up to all Gentiles, with several Greco-Roman ideals of Apotheosis, throughout the Empire (endearing the social classes struggling to survive — blossoming welfare system) takes on an entirely DIFFERENT form than Jesus the Reformer had ever intended! Notwithstanding Jesus’ true pure teachings/reforms, the new Gentile religion was too far gone, popular, and honestly distorted — particularly when the Jewish-Roman War wiped out so many of the outlying sects and those in Jerusalem by 70 CE! Which might have been some of Jesus’ very Jewish 2nd generation followers? Perhaps?

And I am utterly challenged to find out WHY did Paul go to Arabia for 3-years and WHAT was it that he learned there (about Jesus)? Because when Paul returned from Arabia he obviously had a different version of “the Way” and the Kingdom of God than the disciples and the Jerusalem Council had, yes? Any thoughts?

We’ll see what his response will be. Personally, I find Paul’s/Saul’s business in Arabia for 3-years to be very significant in better understanding why and how a floundering Jewish reform movement led by Yeshua/Jesus, suddenly took off 200-300 years later to become the Western Hemisphere’s primary religion. Who better to ask about that than one of the renown experts in biblical history and that era, right?

…

4-4-2018 Addendum — Here was Dr. Ehrman’s reply to my question:

“I don’t think he went into the deserts of Arabia to meditate, reflect, and develop his views. I think he went to the cities of the Nabatean Kingdom (then called Arabia) to begin his missionary work. He claims that he realized the significance of Jesus for Gentiles as soon as he had his vision.”

(paragraph break)

Live Well — Love Much — Laugh Often — Learn Always

This work by Professor Taboo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at www.professortaboo.com/contact-me/.